Interviews decarbonization 7207 26 January 2023

EUROFER Deputy Director General Climate and Energy about the deal on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and review the Emissions Trading System in EU

The EU is moving towards the goal to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Therefore, the block’s institutions reached an agreement to set up the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and review the Emissions Trading System (ETS).

CBAM is a type of carbon pricing for carbon intensive products, such as steel. It is designed to fight climate change and prevent carbon leakage. It will apply from October 2023 with a transitional period until the end of 2025. During this phase there will be a requirement for importers to collect and report carbon data. After the CBAM becomes fully operational, importers will have to purchase carbon certificates. This levy will be linked to the carbon market price in the EU.

Adolfo Aiello, EUROFER Deputy Director General Climate and Energy, spoke with GMK Center about the steps on CBAM and ETS and possible impact on the steel industry in the EU and third countries.

In December, EU institutions agreed on the revision of the Emissions Trading System following an agreement on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. What does the ETS revision set and how will the CBAM work?

The ETS revision sets the rules of the carbon market for the period until 2030. It includes the framework for industry, power, maritime and aviation, as well as the newly established carbon market for buildings and transport. It entails emissions reductions by 62% for ETS sectors by 2030 in comparison with 2005. Consequently, more stringent rules will apply both to auctioning and free allocation.

The CBAM Regulation defines the basic rules for the functioning of this new mechanism, which will require further implementation in the near future. Until 2025 importers will only have to provide data on their emissions intensity, and the actual payment of the CBAM certificates will start as of 2026. The CBAM levy will discount the carbon costs already paid in the country of origin as well as the free allowances granted to European industry, which will be gradually phased out by 2034.

Eurofer warned of risks for EU steel exports despite ETS revision. What is the reason for this risk and how to avoid it?

The risks for the competitiveness of European steel exports stem from the phase out trajectory applied to free allocation. The proposed CBAM will hopefully provide a level playing field on the European market, but in the absence of a solution the European exports will be penalised by the unilateral costs of the EU ETS. We contributed to the debate with different options that could address this risk and be WTO compatible. Both the CBAM and ETS foresee an assessment of the risks for exports by 2025. It will be essential to have a realistic assessment and a concrete and effective export solution by then.

What positive impact of CBAM do you expect for the EU steel sector?

The CBAM is the first-of-its-kind measure addressing unilateral carbon costs. Conditional on the details of its design and implementation, it may contribute to providing a fairer level playing field on the European market by mitigating the risk of carbon leakage. The measure should also provide stronger incentives to decarbonisation in third countries.

Will the CBAM affect the geography of steel supplies to the EU? Which countries will be among the main importers?

The impact of the CBAM on imports will increase gradually overtime. As a matter of principle, low-carbon steel will have a competitive advantage over carbon-intensive steel. Hence, producers from third countries with lower embedded emissions are likely to have better access to the European market. The ultimate impact on the geography of imports will depend also on the ability of non-EU steel producers to decarbonise.

What will be the volumes of steel imports to the EU after the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism begins to operate?

The CBAM is not meant to be a trade restrictive measure, but primarily an environmental measure that ensures decarbonisation incentives for all producers accessing the European market. Moreover, the number of CBAM certificates accessible to importers is unlimited, contrary to the ETS allowances which are subject to a declining cap. Hence, the volume of steel imports will not be determined only by the CBAM, but also by market dynamics and overall trade regime.

What CBAM revenues per year do you forecast? How should it be used?

The CBAM revenues will depend on the carbon price, the volume of imports as well as their carbon intensity. Hence, any estimate is very uncertain. According to the impact assessment by the European Commission on their initial proposal, around €2 billion are estimated in 2030.

How will the CBAM affect the competitiveness of the EU steel sector?

The ultimate impact of the CBAM on the competitiveness of the EU steel industry will depend on the details of its design and implementation. As a matter of principle, it is essential to have an instrument that re-establishes a level playing field for the EU’s unilateral carbon costs and their decarbonisation incentives. This is indispensable in light of the EU climate ambition and subsequent legislation, which entails a very tight carbon market and declining carbon leakage protection through free allocation.

Should the EU refuse the scrap export in the context of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism?

Scrap is indeed a key input for reducing emissions in the steel sector. While the CBAM addresses only the carbon costs stemming from the EU carbon market, other instruments can contribute to higher steel recycling in Europe. Notably, in the framework of the EU Waste Shipment Regulation, it is key to ensure a genuine level playing field between the EU and third countries, especially with respect to environmental, social, safety and health conditions in waste shipment and further treatment. Scrap recycling should follow high climate and social standards equivalent to those we have in the EU, otherwise Europe risks not to reach its environmental and circular targets whilst increasing carbon leakage and exporting waste challenges to third countries.

How can the steps on ETS and CBAM affect green steel?

Both the ETS and CBAM are meant to provide investment signals towards decarbonisation. However, the lack of comparable climate ambition in third countries entails also a very high carbon leakage risk, which may undermine the competitive transition of EU steelmaking towards climate neutrality. Therefore, the two instruments as well as the overall EU regulatory framework need to reconcile the ambitious climate targets with the competitiveness of the steel sector.

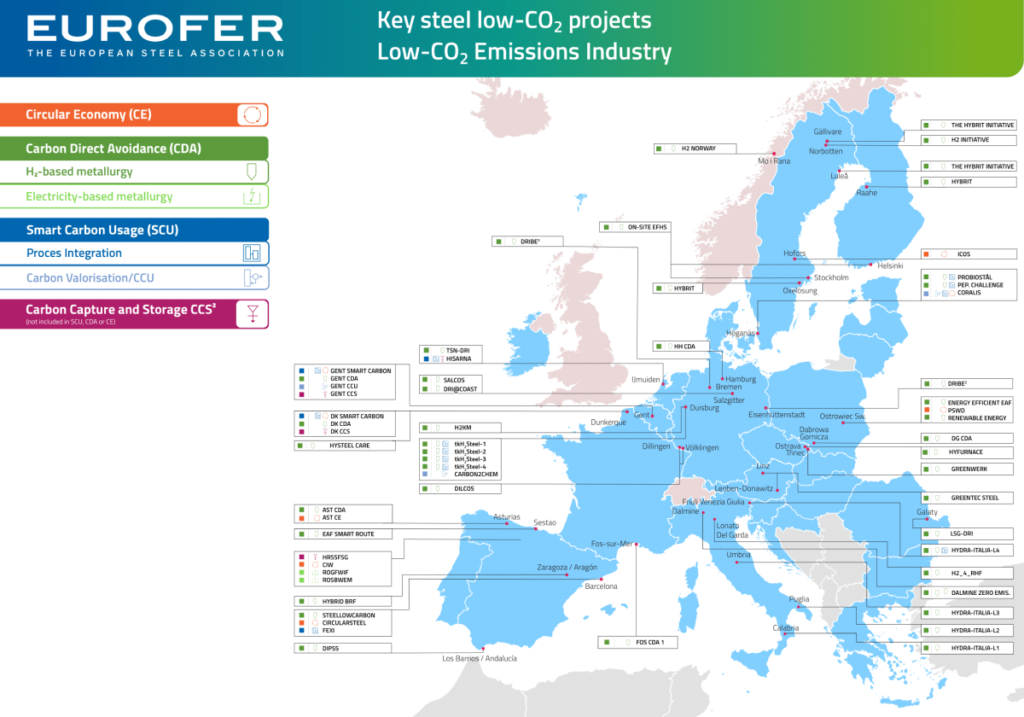

How many low-carbon projects does the EU steel sector have? In what countries do they work?

The EU steel industry is on an ambitious path to cut carbon emissions by 55% by 2030 and to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, in line with the EU climate targets. This is why the European steel sector has developed a large number of low-carbon projects across all major EU steel producing countries, which have the potential of abating CO2 emissions by 81.5 million tons per year by 2030. All these projects – currently 60 in 12 countries (link to the map here) – have a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of at least 7 out of 9. At the moment, their financial needs until 2030 are estimated at €31 billion for capital expenditures (CAPEX) and €54 billion for operating expenditures (OPEX), totalling €85 billion. An overall update is expected in spring.

However, the successful transition of the EU steel industry towards CO2 neutrality depends on the availability of cost competitive fossil-free energy carriers – especially electricity and hydrogen – and related infrastructure, including for CO2 transport and storage. In fact the currently planned low-carbon steel projects will require annually about 75 TWh electricity for the operation of steel processes and about 2.12 million tonnes of hydrogen (corresponding to about 90 TWh of electricity, if this hydrogen is produced via water electrolysis), which means in total about 165 TWh of decarbonised electricity by 2030. This is the double of Belgium’s yearly consumption. Therefore, the success of low-carbon steel projects requires a supportive legislative framework that effectively addresses carbon leakage both during and after their implementation.

Are the ETS and CBAM steps enough to move towards climate neutrality in the EU metallurgy? What else should be done to achieve this goal?

The experience gained from the projects being launched in the last years clearly shows that the ETS and CBAM need to be accompanied by an overall supportive financial, regulatory and energy framework. Firstly, funding support is necessary to untap the unprecedented abatement potential of such projects. Secondly, access to affordable low carbon energy such as electricity and hydrogen is essential for the decarbonisation of the steel sector. Thirdly, carbon leakage protection is indispensable for the industry to remain competitive through the transition. Finally, demand side measures are required to create incentives for customers to use green steel.