Posts Green steel green steel 5257 26 September 2023

Although many companies hope to get “green” steel premiums, but the big question is how sustainable these earnings will be in the future

“Green” premium is calculated as a difference between prices of “green” and conventional products. It shows how much more green products are more expensive than conventional ones. Steel companies believe that customers will be ready to pay more for “green” products when these products will appear at market (it may not happen earlier than in 3-5 years). Moreover, some companies have already launched “green” premium indexes for steel products. But has anyone considered the possibility that the green premiums expectations will not be met?

For us the big question is whether there will be a need to overpay for “green steel” products. The answer depends on two factors. The first one is future dynamics of production costs (both for “green” and conventional products). The second factor is ratio between demand and supply at the market of “green steel” products.

Impact of production costs

The most significant impact on production costs will come from the CO2 and energy prices. We understand that сarbon prices in EU will rise. According to consensus forecast calculated by GMK Center CO2 price in EU will reach €133/t in 2030, while current carbon price is about €90/t.

EU ETS was constructed in a such way that the emission cap and free allocated carbon allowances are being reduced. Moreover, reduction of free allocations will be accelerated because of CBAM introduction. The sharpest reduction in free allocations is expected in 2029-2030 and from 2034 economic sectors under CBAM will not receive any free allowances. All abovementioned reasons will lead to increasing demand for carbon allowances and rising CO2 prices.

Energy prices will differ across different regions. We see that low-carbon projects are concentrated in countries which have access to cheap renewables (Sweden, Norway, Spain, Australia etc.) or cheap natural gas (Middle East). Such strategy is reasonable because it gives competitive advantages to steel producers.

Decarbonization of steel industry is highly dependent on decarbonization of energy supply. First of all, it is connected with the fact that the main decarbonization route is DRI-EAF. EAF work is based on electricity – 90% of costs to produce steel in EAF is affiliated with energy. DRI production needs natural gas and in future – hydrogen. Considering “green” hydrogen, its production also needs supply of renewable energy.

On the one side, we understand that steel market will consist of “green” products and conventional ones. The same type of product can be produced using both green technology and conventional technology. Both “green” and conventional producers will impact on prices.

On the other side, we take the position that steel prices in different segments are defined by production costs of marginal producer. It is that producer, who can still meet current market demand, but whose production costs are maximum.

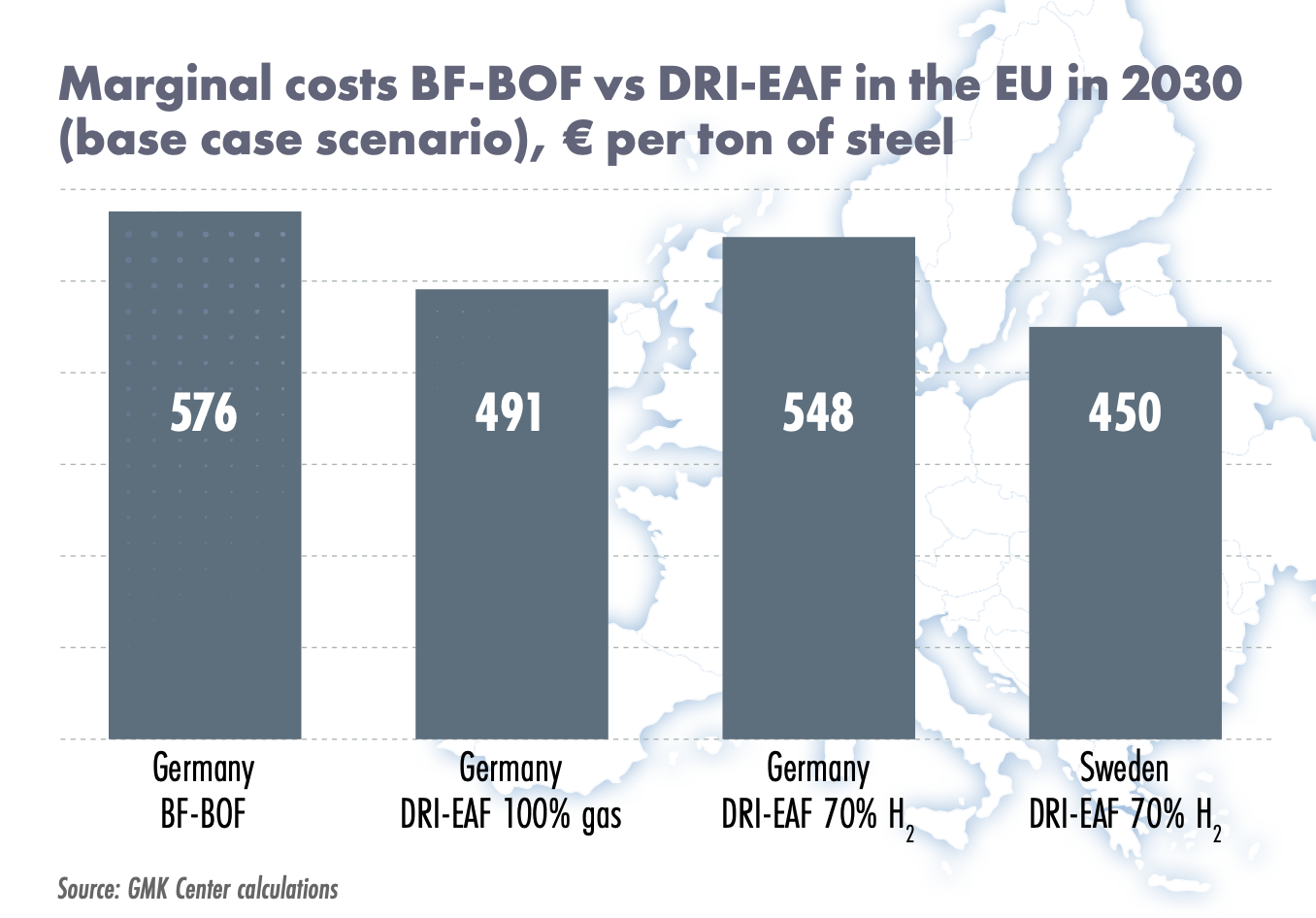

Calculations of GMK Center and other researchers show that difference in production costs and prices of “green” and conventional producers in 2030 will not be so significant to define “green” premium. DRI-EAF production marginal costs using 70% hydrogen in the energy mix will be close to BF-BOF costs, so there will no room for “green” premium.

“Green” premiums are only likely if energy prices are high: electricity – more than €100/MWh, natural gas – more than €100/MWh. In such case more expensive energy will increase production costs of DRI-EAF manufacturers, so it will increase market price of their products. In general, increased energy expenses have a negative impact on the competitiveness of DRI-EAF manufacturers in comparison with BF-BOF. But in the market DRI-EAF manufacturers with higher production costs will set higher prices because we suggest that only BF-BOF supply will not be enough to meet demand.

“Green” premiums also can exist if hydrogen price is high. With low hydrogen prices (less than €2.5/kg) production costs of different technologies (both BF-BOF and DRI-EAF routes) will not significantly differ. Moreover, with low hydrogen price DRI producers from Europe can have an advantage over MENA producers in mixes with a high proportion of hydrogen.

There is an opinion that “green steel” premiums will be linked with carbon market price. Indeed, carbon markets are designed to fix market mistakes. On free market carbon intensive products will cost less than low-carbon ones. So, high carbon price will increase costs of conventional steel products making “green” products more attractive for customers. Suppliers of “green steel” products can receive benefits from high carbon price because it makes conventional steel products more expensive.

Demand side

Considering demand for “green steel”, we must recall that steel holds the major share in total supply-chain emissions of steel consuming industries – from 32% in construction of buildings up to 50% for domestic white goods. So, purchasing of “green” steel could provide opportunities for Scope 3 emissions reduction for steel consumer industries.

We can expect the greatest demand for “green” steel from the automotive segment, which in the EU accounted 16% of steel consumption or 23.3 mln tons in 2022. Automotive industry could decrease its supply-chain emissions by 34% due to purchasing of “green” steel and it will add only 0.5% to car manufacturing costs, based on the share of costs for the purchase of steel in total costs. The same relates to other industries.

“Green” steel purchasing leads to minor changes in costs of steel consumers. In other words, buying “green” steel can bring benefits to consuming industries and they can afford it. But the potential is highly dependent on the specifics of each sector.

High market concentration and pressure from customers will stimulate automotive sector to demand “green” steel from steelmakers. That’s also relates to white goods, where positive perception of “green” products should stimulate producers to buy green steel. Renewables is the industry with image of environmentally oriented business, that put pressure for lowering supply chain emissions.

Sectors that consume 20% of steel in EU or 29 mln tons has high potential demand for “green” steel. Automotive, renewables, white goods consume mainly flat steel products, that usually produced by conventional BF-BOF technology.

On the other side, construction, the largest steel consuming industry, doesn’t experience significant pressure to decrease emissions on lack of policies. It has also low market concentration. Construction consumes mainly longs products, that usually produced via scrap-based EAF route and doesn’t have significant potential to reduce emissions by purchasing “green” steel.

Reducing supply chain emissions is an important part of manufacturing business decarbonization strategies. The largest market operators have targets to reduce Scope 3. But the share of supply chain emissions in Scope 3 of automotive and domestic appliances industries is relatively small – up to 18%. Companies have a greater incentive to move towards their Scope 3 reduction targets in other ways. For example, automotive companies – due to the focus on the production of electric vehicles. Manufacturers of home appliances – at the expense of renewable energy sources.

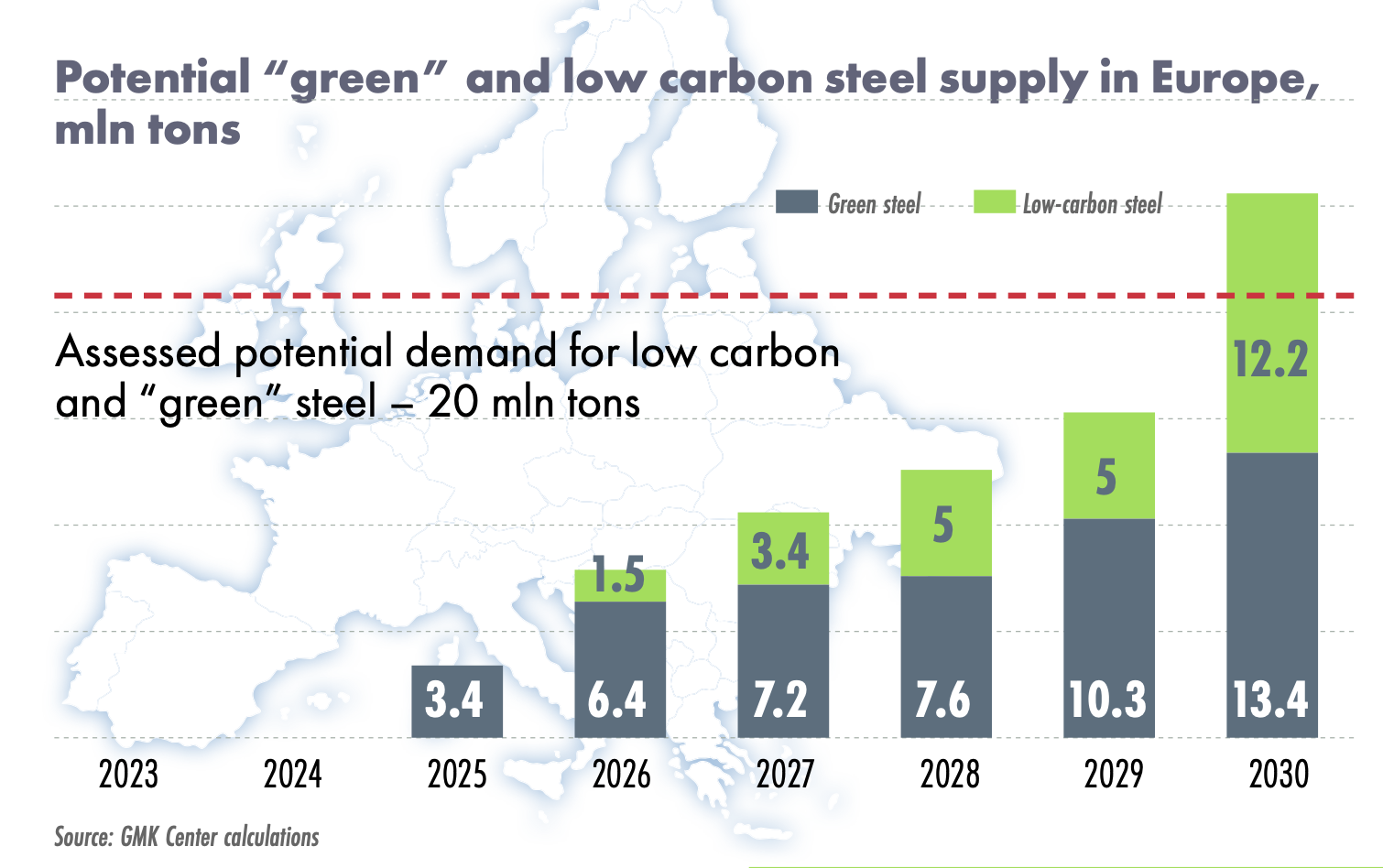

Therefore, we consider that until 2030 the green steel consumption potential could be realized only partially, in the amount of up to 20 million tons of steel in terms of finished products. It will also depend on commercial issues – “green” steel prices, premiums.

Comment: GMK Center in calculations separated low-carbon and “green” steel based on carbon intensity. Carbon intensity of “green” steel is 0.25 t CO₂, reflecting the maximum allowable share of hydrogen in 80% and 20% of the natural gas. Low carbon steel can have carbon intensity from 0.26 tons to 0.6 tons per ton of steel.

“Green steel” supply

Since the DRI-EAF route has become the leading decarbonization technology, we expect that main part of “green steel” supply will come from DRI-EAF producers. 26 projects announced globally with a total capacity of 67 Mt DRI/HBI. Particularly in Europe – 16 projects with a capacity of 40 million tons, which is 50% of the current volume of BF-BOF steel output. The companies implementing DRI-EAF projects include both integrated plants and new entrants (H2GS, GravitHy, BlastrGreenSteel). All projects of the integrated plants are captive, and the new entrants are partly oriented to the European HBI merchant market as well as to the production of finished steel products.

Existing technical solutions make it possible to use hydrogen as a reducing agent in the production of DRI/HBI, including as part of a mix with natural gas. Some of the projects initially declared 100% hydrogen usage as a reducing agent, which we consider as “green” HBI for further production of “green” steel. These projects are AM Hamburg, AM Sestao, Thyssenkrupp, Salzgitter, H2GS in Boden and Iberia, SSAB HYBRIT, GravitHy, BlastrGreenSteel.

The supply of green steel by 2030 may exceed 25 million tons, based on the announced projects and their 85% utilization. By 2030, we expect no shortage of supplies, which eliminates the possibility of establishing “green” premiums.

Also worth adding there is no recognized certification or classification for low carbon and “green” steel in the world.Therefore, the branding factor in marketing promotion of low carbon steel can be widely used. In other words, all low carbon steel producers will call their products “green” using brand-names for their products. So, all customers, which will need “green” steel, will be able to find appropriate “green” product.

Some potential producers of low-carbon steel announced that they have reached agreements with buyers on a green premium. Some producers and market researchers believe that “green premiums” can reach €200-300/t. We do not deny that “green premiums” can exist, especially at the first stage of “green steel” market evolution. First producers of “green steel” can receive “green premiums” for a short time until market supply will increase. Then we think “green steel” premiums will not be sustainable practice.