Posts Global Market CBAM 1920 26 May 2025

Ukrainian industry insists on urgent action to delay CBAM for the country

The global market is preparing for the final implementation of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) from January 1, 2026. The EU and the UK have recently announced an agreement to merge the two ETSs, a move that was expected and whose benefits and drawbacks have been discussed by British businesses since last year. Some major economies are still choosing the path of confrontation. At the same time, Ukrainian industry insists on the need to postpone the mechanism for the country, as the consequences of the CBAM for the Ukrainian economy and export-oriented industries could literally be devastating.

UK – EU

On May 19, the UK and the EU pledged to work on unifying their emissions trading systems (ETS). This agreement was reached as part of a broader deal between the parties that resets post-Brexit relations in areas such as fishing rights, trade, and defense.

“Closer cooperation on emissions by combining our respective systems will improve the UK’s energy security and avoid hitting businesses with the EU carbon tax due to come into force next year, which would send £800 million ($1 billion) directly to the EU budget,” the British government said in a statement.

British industry operated under the EU ETS until the country left the bloc and launched its own carbon market in 2021.

Last summer, Frontier Economics, a consulting company commissioned by key players in the British energy market, released a study on the loss of revenue if the country remains outside the EU carbon market – it was about the amount of up to £8 billion ($10.2 billion) in 2025-2030.

The move announced by the parties was welcomed by the UK Steel industry association. It noted that it has been advocating for the unification of carbon markets since 2019, as the separate British one was too small and illiquid. The announcement made by the parties provides for mutual recognition of carbon emission quotas. This will create a single price for CO2 in both markets and free UK steel exports to the bloc from the costs and administrative burdens associated with CBAM.

In general, the ETS agreement will aim to enable reciprocal exemption of goods originating in the two jurisdictions from the EU and UK CBAM obligations and should cover sectors such as electricity generation, industrial heat production, industry, maritime transport and aviation, with a procedure to expand the list.

In April, the UK published draft primary legislation for its own CBAM (the mechanism is due to enter into force on January 1, 2027).

British industry has long called for linking the country’s carbon market to the European one. However, analysts warn that the merger of the systems is likely to lead to an increase in carbon prices in the UK to the level of European ones, with critics citing a figure of 6%.

On May 19, after the announcement of the merger, the cost of UK benchmark carbon contracts rose by 8.4% to £52.4/t (€62.3). So in the short term, the deal could mean an increase in the carbon burden for British companies.

The path to simplification

As the full implementation of the European CBAM from the beginning of 2026 will have a serious impact on global trade, exporting countries are choosing different tactics to respond. Some countries are developing their own analogues or adapting domestic pricing tools, while others are consistent opponents of the European scheme, including China and India. For example, India has recently announced that it will retaliate if the EU goes ahead with its plan to levy a carbon tax on Indian products. This was stated by the Minister of Commerce and Industry Piyush Goyal. The parties are currently negotiating a free trade agreement (FTA), aiming to finalize it by the end of 2025. A mechanism for cross-border carbon adjustment is also under discussion.

On May 19, Russia requested WTO consultations on CBAM, arguing that it is not a genuine environmental measure, but “a tool for trade restriction and discrimination.” Other countries have previously promised to take this step.

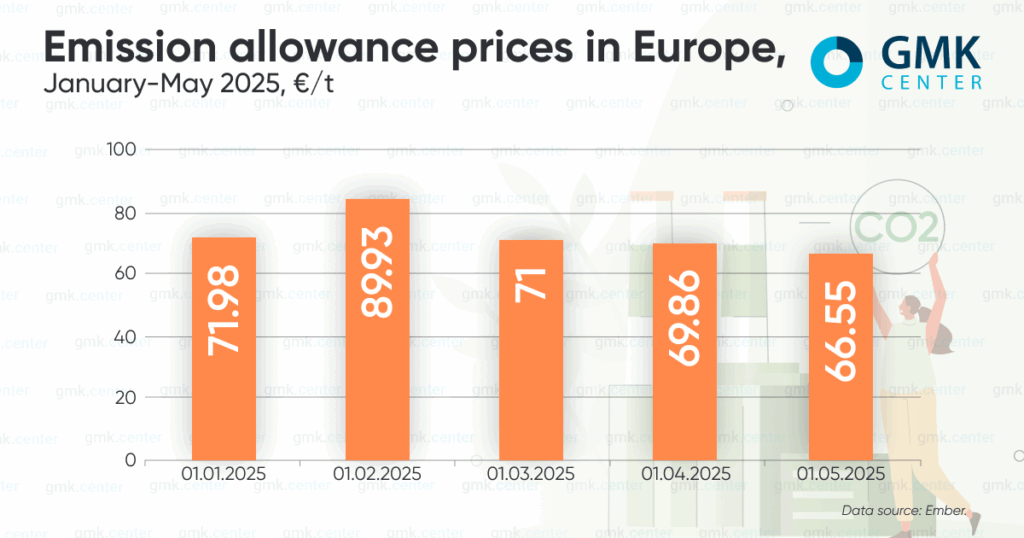

European companies have their own reservations about the mechanism of cross-border carbon adjustment. These include the work of national authorities, administrative procedures, coordination of emissions tracking in the supply chain, forecasting financial costs in the absence of an understanding of the average price in the EU ETS in 2026 and the yet-to-be-determined benchmarks for calculating the tax, etc.

The European Commission has already proposed simplifying the mechanism as part of the Omnibus I package presented in February.

In May, the European Parliament’s Committee on the Environment, Climate Change and Food Safety supported these proposals, with only technical amendments and a number of other items:

- a new minimum weight threshold of 50 tons, which will exempt 90% of importers (mainly small and medium-sized enterprises and individuals) from the CBAM carbon tax,

- simplification of authorization of declarants, calculation of emissions,

- reporting requirements and compliance with financial obligations,

strengthening the anti-circumvention strategy.

After the vote, speaker Antonio Decaro said that the majority of the committee agreed to limit the amendments to specific EC proposals and not to revise other provisions of the CBAM legislation. According to him, this approach allows simplifying the work of companies without abolishing or weakening the mechanism.

On May 22, the European Parliament approved the same proposals to simplify CBAM, including a new de minimis weight threshold of 50 tons. Now, the bloc’s legislative body must start negotiations with the European Council on the final text. And in early 2026, the EC will assess whether to extend the scope of the mechanism to other ETS sectors where there is a risk of carbon leakage.

At the end of March this year, the call for applications from importers to become an authorized CBAM declarant was opened – in parallel with the development of the IT system for the registry, so that the latter is fully operational by January 1, 2026. The EC is also working to further simplify the mechanism. In particular, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union (TAXUD) has convened an informal expert group on these issues, which has met three times, most recently in May this year.

An exception for Ukraine

At the same time, the final introduction of the CBAM could deal a devastating blow to Ukrainian producers. According to GMK Center’s updated estimates, Ukraine could lose $7.2 billion in GDP by 2030 as a result of the mechanism. In 2024, the country exported $24.8 billion worth of goods to the EU, of which 14.5% fell under the CBAM. The metallurgical sector will suffer the most, having supplied $3.3 billion worth of products to the bloc.

Therefore, the country’s industrialists and industry associations insist that the government immediately appeal to the European Union to postpone the mechanism for Ukraine on the basis of Article 30(7) of Regulation (EU) 2023/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council as a basis for force majeure. Such calls were made, in particular, by the Association of Environmental Professionals (PAEW) and the Office of Sustainable Solutions, Ukrcement Association, the National Association of Mining Industry of Ukraine and leading participants of the subsoil use market, the Federation of Employers of Ukraine.

The domestic industry criticizes the wait-and-see approach taken by the Ukrainian authorities, as the initiative of transboundary carbon adjustment is spreading around the world. It was surprising that Ukraine did not ask the EU to postpone this environmental duty, as stated in the European Commission’s official response to the EBA’s request, which was published in the media on April 29.

In the end, according to Taras Kachka, Deputy Minister of Economy and Trade Representative of Ukraine, the government is currently preparing official appeals to the European Commission to grant exemptions for the country as a whole and for electricity exports separately, which will be worked on in the coming months.

“We have been engaged in a dialog with the European Commission for quite some time, trying to understand how it should work. That is why we are already moving into the active phase of work on the CBAM exception for Ukraine,” he said.

The Ukrainian mining and metals industry has repeatedly emphasized that it is ready to contribute to the “green” transition in the European steel industry by supporting supply chains. However, in the context of a full-scale war, the industry does not have the capacity and funds to modernize accordingly. In addition, domestic producers do not have access to the same financing terms and grants as European industry.