Posts Global Market India 405 07 July 2025

The country's government began the transformation by establishing a legal and regulatory framework

Indian steel industry is the most promising in the world today in the context of green transition. In terms of steelmaking growth rates, India leads the top 10 largest steel producing countries by a wide margin. This is despite modest export volumes and still significant imports of finished steel. Strong domestic demand in the world’s fifth largest economy has been keeping the global steel consumption rate from falling for months now.

At the same time, India emits 2.54 tons of CO2 per 1 ton of steel, compared to the global average of 1.91 tons. So, the potential for their reduction is enormous. And in one very important aspect, Indians are already ahead of the rest. For the first time in the world their steel has received ecological classification at the state level. This has created a regulatory framework for the forthcoming “green” transition.

Step One: regulation

The Ministry of Steel of India (MSI) on March 21, 2025, published the Green Steel Taxonomy. It will come into force in fiscal year 2026–2027 and establishes three rating categories. To be assigned a rating, the steel produced by an enterprise must meet the following criteria:

- 5* – emissions must be less than 1.6 t of CO2 per 1 t of finished steel;

- 4* – for emissions of 1.6–2.0 t of CO2;

- 3* – for emissions of 2.0–2.2 t of CO2;

When summarizing the categories, Scope 1 and Scope 2 are fully accounted for, Scope 3 is partially accounted for. This section includes CO2 emissions from coke production, sintering and sintering of iron ore, pellet production and transportation of raw materials.

The National Institute of Secondary Steel Technology (NISST) will be responsible for assigning ratings and issuing certificates. Rating criteria are subject to revision every 3 years. Creation and maintenance of the state register of green steel on the basis of NISST conclusions is entrusted to the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE).

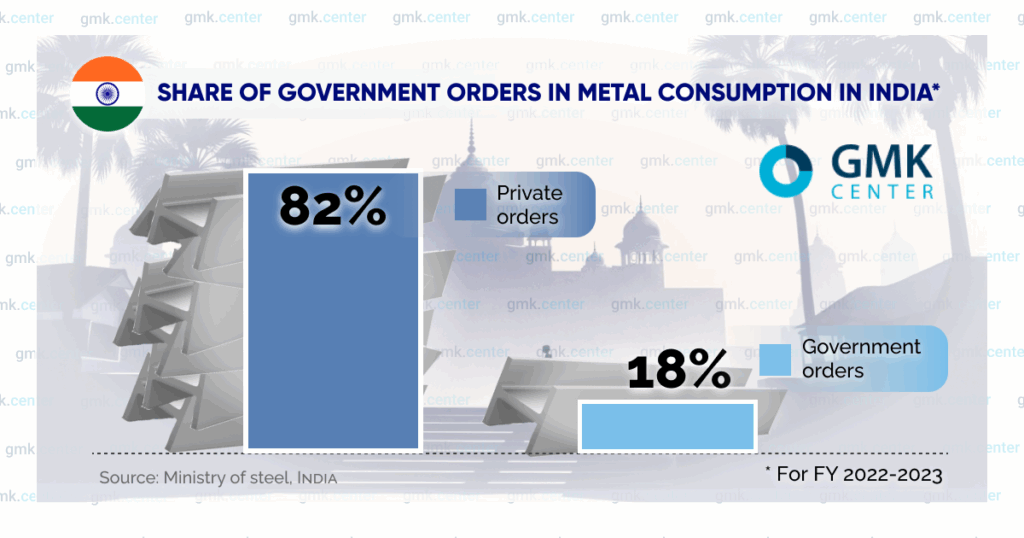

The authorities intend to prioritize such steel under MSI’s Green Government Procurement Policy (GPP). This is an important incentive, given the significant role of the government in overall steel consumption.

According to MSI, in the 2022–2023 fiscal year, public procurement of steel products reached 25 million t. By the 2030–2031 fiscal year, it will increase to 67–73 million t.

Step two: optimization

India plans to achieve zero CO2 emissions in its economy and, consequently, in its steel industry by 2070. But it is realistic. According to the Ministry of Steel, the cost of the issue for the industry is $283 billion. This is the money needed only for existing steel plants with a total annual capacity of 200 million tons. Without taking into account additional costs for new plants with a capacity of 300 million tons, which are planned to be built by 2047.

But here we are talking about the ultimate goal – completely emission-free production. In fact, Indian steel should become “green” much earlier. And it will cost “only” $13 billion. This is the amount estimated for the introduction of improving technologies. First of all, in terms of energy efficiency. At present, specific energy consumption of Indian steel mills using BF-BOF technology is 6-6.5 GKal per 1 ton of steel, while for DRI-EAF/IF technology it is 7 GKal, while the world average is 4.5-5 GKal.

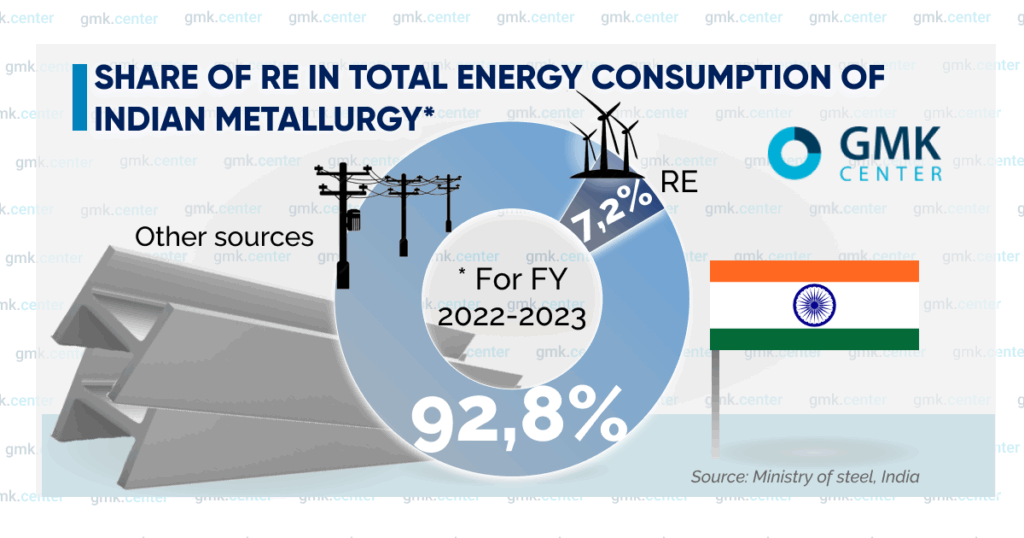

The ministry sees ways to reduce this figure in the digitalization of production processes. Plus a shift to renewable energy sources (RES). Currently, the Indian steel industry receives only a small part of its electricity consumption from renewable energy sources.

By FY 2030-2031, the rate should reach 43.33%. This alone will reduce specific CO2 emissions from the current 2.54 tons to 2.35 tons per 1 ton of steel. It is well known that renewable energy is much more expensive than coal-fired power plants. It is planned to make it more affordable by waiving the fee for electricity transmission.

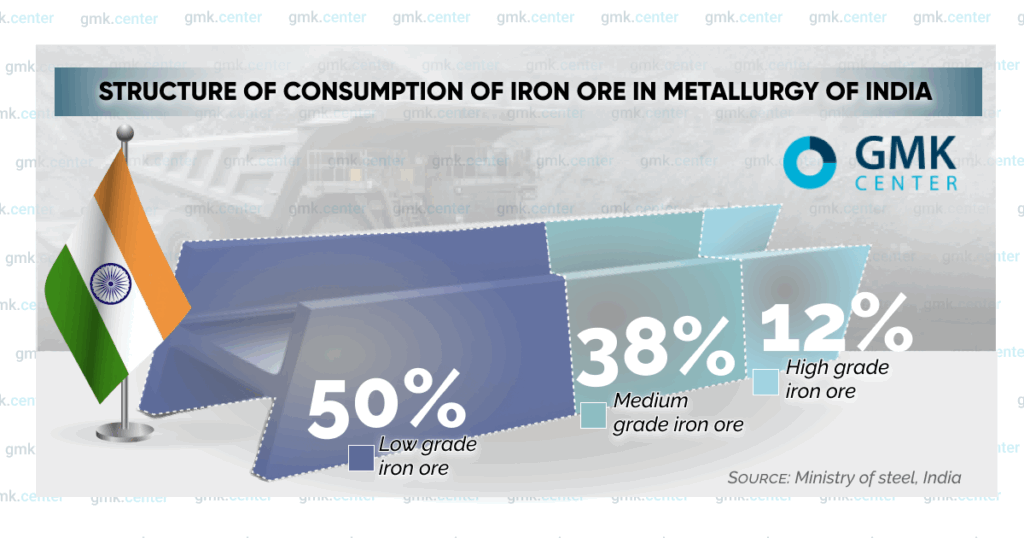

Among other directions it is possible to note increase of efficiency of materials for Indian steel industry. Currently, it mainly uses low-grade iron ore.

MSI calculates that a 1% increase in Fe content in iron ore increases blast furnace productivity by 2% and reduces coke consumption by 1%. This is achieved through additional beneficiation or pelletizing of iron ore.

How realistic are these plans? ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel India intends to bring its steel products to 70% compliance with green criteria by FY 2026-2027, i.e. in the near future. Already now the company has a CO2 emission rate of 2.17 tons per 1 ton of steel. By 2030 it should be reduced to 1.8 tons. So it is quite possible.

At the same time, it is obvious that although the 5* category for Indian green steel implies rather high emissions (compared to the USA, the world leader in steel decarbonization), they are not achievable for mills with BF-BOF. For example, the same ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel India will not be able to get 5* for all products in 2030. Therefore, next steps are needed.

Decarbonization tools

Unlike the US, which has opted for R-EAF scrap based and the EU, which has opted for H2-DRI-EAF, India, in its Roadmap for Greening the Steel Sector, does not define a technology pathway for decarbonization. It is open to utilizing all possible options. This flexibility is certainly an advantage of New Delhi’s strategy.

Today, electric arc furnaces account for 30% of India’s steelmaking capacity. At the same time, their utilization is lower than that of BF-BOF mills – 74% and 84% respectively. Among the new plants with a total capacity of 258 million tons per year at the stages from design to implementation, the share of EAF is 13%, or 33.54 million tons. Here we can highlight the construction of Tata Steel’s plant in Punjab with a capacity of 750,000 tons of steel per year. And state-owned SAIL’s project to build a plant with EAF with a capacity of 1.5 million tons of steel by 2029.

By 2047, the Steel Ministry has declared intentions to increase the share of scrap in steel production from 15% to 50%. This will require additional supplies. It is planned to obtain them at the expense of imports. At the same time, India is already one of the world’s largest importers of scrap, 9.39 million tons by the end of 2024. Obviously, in the future, the figure may double. Now imports cover about 25% of the demand for this resource. Domestic scrap collection is about 25 million tons.

However, MSI notes the difficulty of securing future production in an environment where more and more countries are restricting or even outright banning scrap exports. India is therefore pursuing a strategy to increase domestic scrap collection. As part of this, major steelmakers such as SAIL and Tata Steel are investing heavily in their own scrap collection.

The authorities also have plans to create a nationwide electronic platform for scrap trading. This should contribute to the “detanization” of the Indian scrap industry. In addition, a program offering incentives for scrapping to owners of used cars is already in place. And the possibility of restricting the export of steel scrap is being considered. The volumes of which, however, are small: 8,175 containers in 2023-2024 FY.

Another option is CCUS technology to capture, recycle and store CO2. The Indian steel industry has several pilot projects for CO2 capture. But they are unprofitable right now. MSI estimates the current cost of capture at $45-60/t. For steel mills, the acceptable price is less than $20/t. And utilization and storage costs another $300-500/t. In this case, the price of finished steel will rise by 100%. Therefore, technological solutions are being sought to make CCUS more affordable.

It is well known that India is the world leader in DRI production. But only 5% of the kilns are powered by natural gas. The rest are coal-fired. Therefore, another way to reduce emissions is to gasify this production. This is the path Jindal Steel has taken. The company has built a coal gasification plant at its plant in Odisha. The resulting synthetic gas is used to recover iron in pellets to 99.99%.

Overall, the government aims to achieve an annual coal gasification capacity of 100 million tons by 2030. To this end, state-owned Coal India Ltd (CIL) has formed joint ventures with Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd and Gas Authority of India Ltd (GAIL). Government funding of 3.61 billion is being allocated for the respective projects.

And then there is hydrogen. Namely, replacement of coke and coal with H2 in furnaces for iron smelting and DRI production. This area is still in the pilot stage. Tata Steel in April 2023 conducted a successful trial hydrogen injection in a blast furnace at its Jamshedpur mill. And in February 2025, i.e. 2 years later, the company announced the development of special steel pipes to transport gaseous H2 at high pressure.

You can see that the work is not progressing too fast. But in fact, there is no point in Tata Steel and other steelmakers forcing technical changes. Because the hydrogen industry itself is slow to develop.

The National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM), adopted in January 2023, envisions 5 million tons of the product by 2030. However, it was only in late June this year that the Adani Group Corporation was able to commission the country’s first 5 MW electrolyzer plant in Gujarat. This year, JSW Group is also expected to commercialize an H2 plant with an electrolysis capacity of 25 MW in the state of Karnataka.

Thus, the NGHM target by 2030 will definitely not be achieved. The reason is that the production cost of H2 is too high. It is now $4.6-6.3/kg, according to the Institute for Energy Economics&Financial Analysis. This year the government canceled the fee for transmission of electricity, reduced the tariff for distribution of electricity and VAT for producers of green hydrogen. Due to these measures, according to IEEFA estimates, the cost of production is reduced to $3-3.75/kg.

But this is not enough. According to the Steel Ministry, a price in the range of $1/kg would make it commercially viable for Indian steel mills to use H2. In this case, they will be able to consume about 1.1 million tons per year. Therefore, obviously, the government will have to look for additional mechanisms to reduce the cost of green hydrogen production.

Overall, MS calculations show that decarbonization of Indian steel industry is realistic. With a green premium of 30% to the price of conventional products, with the replacement of 20% of BF-BOF production with emission-free production – green steel will increase the cost of infrastructure projects by only 1.1%, production of cars and household appliances – by 0.5-1%. In such a case, the industry’s green transition will be paid for at the expense of end consumers.