Posts State privatization 3332 21 December 2023

The consequences of the war and related problems will likely override the state's ambitions to sell strategic assets in 2024

Since the beginning of the full-scale war, privatization in Ukraine has been suspended for the period of martial law. However, small-scale privatization (objects worth up to UAH 250 million) was unblocked through the adoption of draft law No. 7451 in late July 2022 and resumed in September 2022. The resumption of large-scale privatization (worth over UAH 250 million) became possible after the adoption of draft law No. 8250 in late May. Such a rush to resume privatization in the current environment may be surprising, to say the least.

But the main problem is the high risks – the vulnerability of privatization objects to Russian missiles and UAVs, which makes it unlikely that investors will be interested in the privatization and that assets will be fairly valued. In addition, the constant postponement of privatization deadlines does not add to the confidence of potential investors in the Ukrainian authorities.

Overstated ambitions of the state

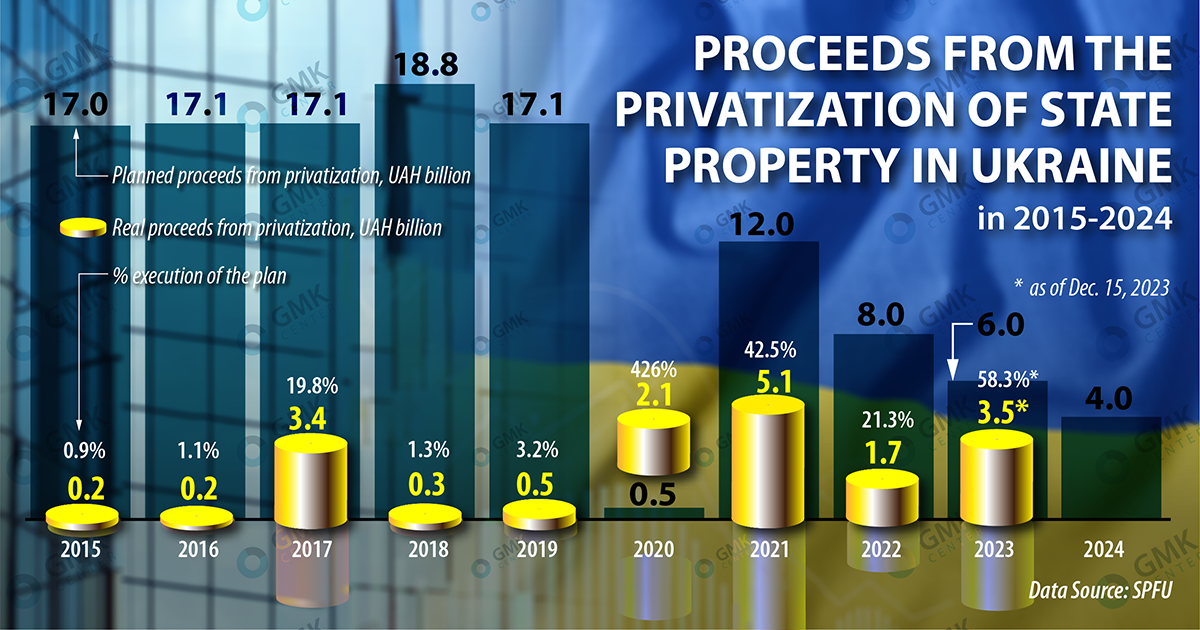

As a rule, the targets included in the state budget do not coincide with the actual privatization proceeds. From year to year, the number of revenues is significantly lower than expected. As of Dec. 15, 2023, the State Property Fund of Ukraine (SPFU) attracted UAH 3.5 billion to the state budget, and although the state budget for 2023 planned to receive UAH 6 billion. All funds will be used to support the Defense Forces. Therefore, this year’s revenue plan will not be fulfilled, although the percentage of fulfillment will be higher than in 2022. It is worth reminding that in 2022, the revenue expectations were UAH 8 billion, but due to the war and the suspension of privatization, only UAH 1.7 billion was actually received.

In January-September, SPFU held 303 successful auctions. More than 60% of the lots were commercial real estate for opening a shop, office or cafe. The most expensive lot this year was the Hermitage Hotel in Kyiv, which was sold for UAH 311 million. However, distilleries have been a hit in recent years. From the fall of 2020 to the beginning of 2023, 39 electronic auctions were held, bringing more than UAH 2 billion to the budget.

In 2024, the SPFU plans to put up for privatization about 1000 objects and sell state property for UAH 4 billion, including 15 large and more than 300 small objects. Minimum proceeds from small-scale privatization are expected to reach UAH 1 billion.

Problems with privatization during the war

Privatization plans for 2024 provide for the following assets to be put up for sale:

- Odesa Port Plant (OPP),

- Centrenergo,

- United Mining and Chemical Company (UMCC),

- Demurinsk Mining,

- Electrovazmash,

- Sumikhimprom,

- Oriana,

- hotel Ukraine,

- Ocean Plaza Shopping Center,

- Indar and others.

On the one hand, the state’s desire to get rid of valuable assets before the active phase of hostilities is even over looks strange. On the other hand, the state has already announced the privatization of these facilities so many times that another postponement of the auctions, for example, to 2025, would not look strange. For example, the government included UMCC in the list of companies to be privatized in 2016, then the privatization was postponed several times, and the tender was twice disrupted. Even within the current year, the SPFU’s privatization plans are constantly postponed. Thus, the SPFU wanted to sell UMCC and Demurinsk Mining and other large assets by the end of 2023.

There are at least several reasons why mass privatization in 2024 is not a good solution.

- In a time of war, it is questionable whether investors are interested in assets that are under constant threat of missile attacks throughout the country and in the frontline regions in particular. Several of the above facilities (OPP, MAP) have already been partially damaged by Russian shelling.

- In the current environment, privatization will either not arouse the interest of investors at all or their list will be very limited.

- Even in the presence of interested investors, the state will not be able to get an adequate price for its assets in wartime conditions.

- In the context of the war and related problems (potential problems with energy supply, logistical difficulties, etc.), it is difficult to count on stable operation of industrial assets even if there is a strategic investor and successful privatization.

The list of large enterprises for privatization may be significantly expanded by confiscated Russian assets. The SPFU continues to prepare these objects for privatization at auctions, although the prospects for their sale are not clear. For example, the first auction for the sale of sanctioned assets – Investagro – did not take place in August due to the lack of potential buyers.

In 2024, we can expect significant demand for small-scale privatization objects and distilleries that have not yet been sold, but investor interest in large assets seems doubtful in the current environment, which is partly confirmed by the SPFU’s constant postponement of the deadlines for putting them up for privatization.

Steel privatization

The list of large-scale privatization enterprises includes a significant number of steel assets, including UMCC, Demurinsk Mining, Zaporizhzhia Titanium and Magnesium Plant (ZTMP), Sumykhimprom, Zaporizhzhia Aluminum Production Plant (ZAP), and Mykolaiv Alumina Plant (MAP).

What is interesting about these companies:

- UMMC and Demurinsk Mining produce ilmenite concentrate, a raw material for the titanium industry;

- ZTMP is the only producer of spongy titanium in Europe;

- Sumikhimprom – a producer of titanium dioxide;

- ZAP is the only producer of primary aluminum;

- MAP – production of alumina – raw material for the aluminum industry.

However, a legal issue may become a potential problem. ZTMP has been returned to state ownership (previously owned by sanctioned businessman Dmitry Firtash), while ZAP and MAP were confiscated from Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska. Demurinsk Mining was confiscated from Russian oligarch Mikhail Shelkov. Confiscation of assets can theoretically be challenged in court. This was the policy pursued by Dmitry Firtash with regard to ZTMP, and it is not known whether he will continue to pursue legal action in the future.

There are other problems as well – for example, ZAP stopped producing primary aluminum long ago, and it will require huge investments to restart it. Currently, the company’s main sources of income are leasing property and selling assets. The situation at ZTMP is somewhat similar, though better. In addition, the assets that were taken away from Firtash – ZTMP and Sumikhimprom (the plant was state-owned but operated by the businessman) – are burdened with debts.

Given the general situation in the country, the martial law and the specifics of the steel assets offered for privatization, it is difficult to predict any demand. In a time of war, potential investors are understandably reluctant to disclose their intentions, and the flow of pseudo-positive information from the SPFU about plans to put assets up for auction is not relevant or even appropriate. It is unclear who the SPFU wants to make feel positive when all the circumstances are against the plans for large-scale privatization and the Fund’s “unpunctuality” is well known.